The Apollo GT. Many are unaware of this Ferrari contender, 88 examples of which were built – by hand – in Italy and assembled in Oakland, California during 1963-65…

In 1960, a trio of Northern California twenty-somethings saw that imported sports cars had a major deficiency: while they were admired by enthusiasts for their exotic styling and hot performance, (especially the Italians), imported sports cars had also developed a nasty reputation for being less than trustworthy.

Indeed, it was a very brave man who dared to drive his Jaguar or Alfa Romeo too far from home; it would break down at the worst possible moment. A cross-county trip was out of the question.

Commuting to work was also a questionable activity, as anyone who’s seen an old Jag in five o’clock traffic can attest to. And if it was a Ferrari? Never.

So, Milt Brown, Ron Plescia, and Ned Davis combined their resources to create a fast, powerful gran turismo in the tradition and style of Ferrari and Maserati, but with the room, reliability, and serviceability of a Buick.

In high school, Brown and Plescia had already “designed” dozens of such cars (when they should have been studying!). After college, Brown took his enthusiasm to Europe where he worked as an engineer for Emeryson, a small race car builder in England. There he gained valuable experience designing chassis and suspensions. During his free time, he searched for a possible coachbuilder for this Euro-American grand touring car.

Back in the States, Ron Plescia, newly matriculated from the prestigious Art Center of Pasadena, was already honing his skills as a product designer.

Partner number three, Ned Davis, held a business degree from the University of California at Berkeley and had his hand in a number of small enterprises. As a small business owner, Davis learned all about cash flow management and promotion – with limited budgets, he had to do it all himself. This would come in handy as the project progressed.

While in Europe, Brown by chance met Frank Reisner, an engineer and owner of the coach building firm Carrozzeria Intermeccanica in Torino, Italy. While Brown found other such suppliers to be frightfully expensive to build a prototype ($50,000 or more – nearly $350,000 in 2006 dollars), he discovered Reisner could do the job for a mere five grand. Striking a partnership with Reisner with a mere handshake, Brown returned from Europe in the Fall of 1960 to begin serious work on a new Italian-American GT.

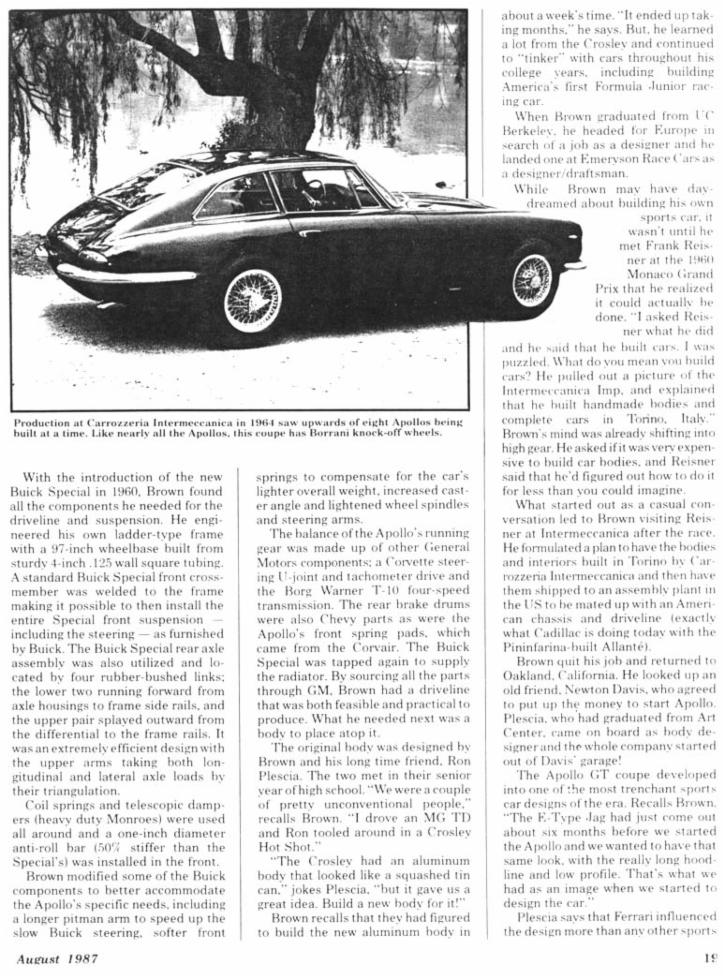

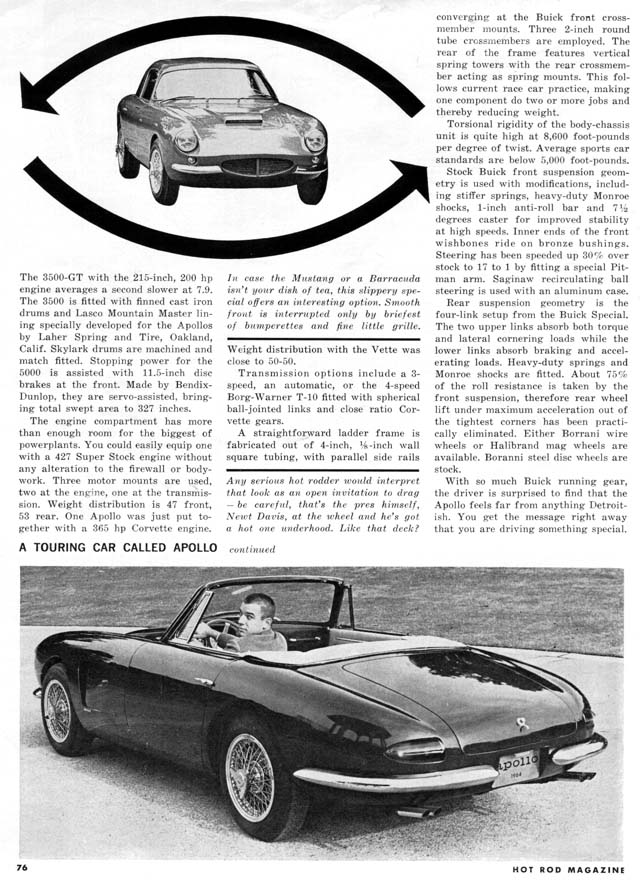

In two weeks, Plescia drew a curvaceous body reminiscent of the Ferrari 250 Speciale, with a hint of Jaguar E-Type (“We wanted a car with Italian styling but with E-Type proportions,” recalls Brown.) and hand molded a 1/4 scale fiberglass model from which Reisner would construct a prototype.

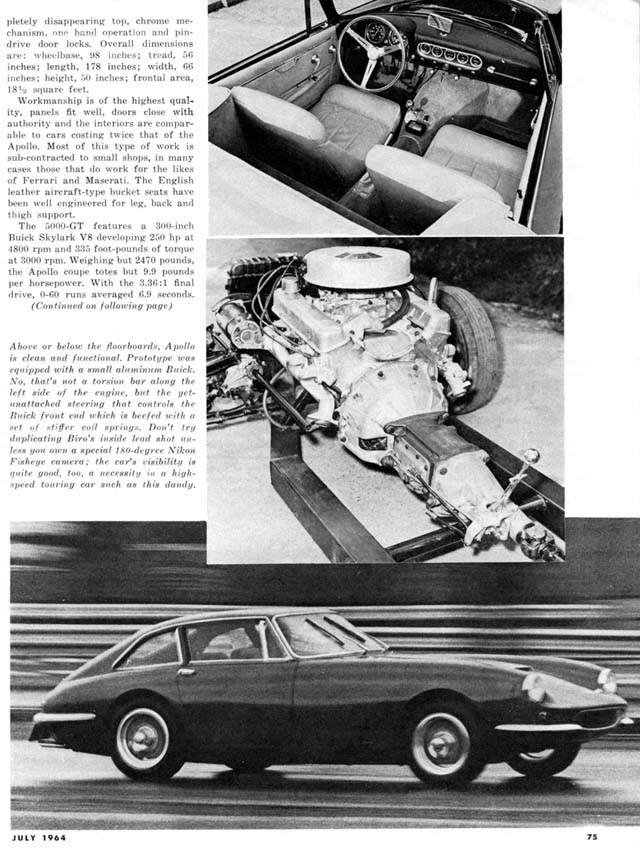

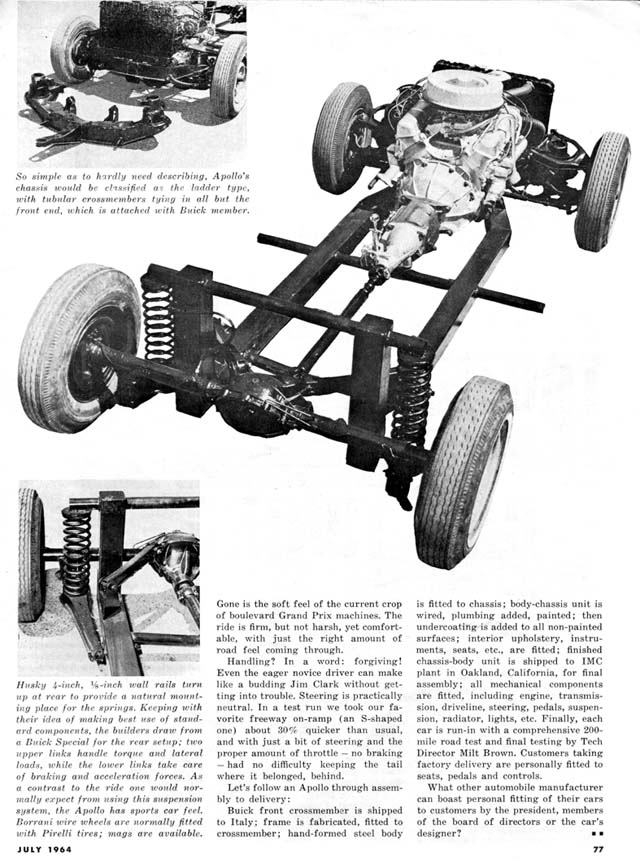

Meanwhile, Brown found an outstanding American car upon which to base this GT: the 1961 Buick Special, a Detroit compact that offered a really advanced suspension for its day. While Ferrari and Maserati still used “cart” (leaf) springs on a live rear axle, the Special utilized a very sophisticated four-link trailing arm suspension – with coil springs – on a live axle. The unit was not only lighter, but offered better handling.

Brown tied the whole package together with a very simple – yet light-and-strong – ladder frame.

For motivation, the new Buick 215 cubic-inch aluminum V8 was not only European in specification (3.5 liters and only 318 lbs. dry) but also powerful: 200 b.h.p. as supplied by GM; 225 when tweaked by Brown. Coupled with the silky smooth Borg Warner T-10 four-speed gearbox, the new car had plenty of go. Early literature (written and produced by Ned Davis) claimed acceleration times of 0-60 in 7.5 seconds and a standing start quarter mile in 15.6 seconds. Top speed could reach 140 with the optional 3:08 rear axle. Very competitive performance.

It was Ned Davis who supplied the $5,000 to pay for the prototype. The trio shipped Brown’s new chassis, along with Davis’ money, to Intermeccanica in December, 1961. In August the following year, the aluminum bodied prototype arrived in Oakland, and Brown and Davis readied it for its debut at Bev Spencer Buick in San Francisco. The public’s reaction was so favorable that Brown, Davis, and Plescia decided to go ahead with production and incorporated as International Motor Cars of Oakland. But the new company was woefully undercapitalized with only $21,000 in the bank, donated by family members and friends. “We knew it wasn’t enough,” recalls Ned Davis. “But we thought we’d get enough orders to stay in business. Besides, a chance like this only comes once in a lifetime.”

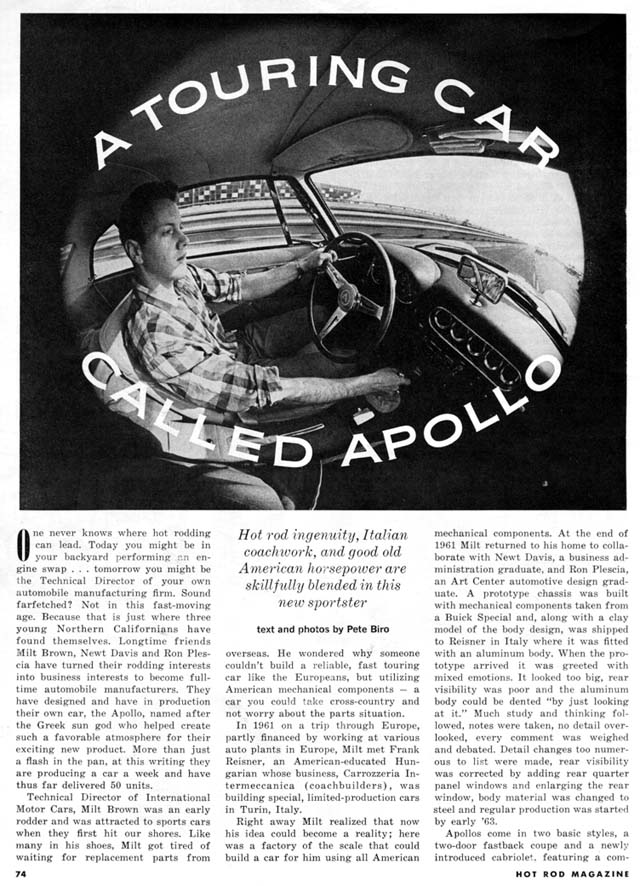

With a firm commitment for two cars per month, Frank Reisner geared up to build, paint and trim Apollo bodies in steel and called in the famed Franco Scaglione (designer of the Bertone B.A.T. show cars) to tweak the design and ready it for production. The same artisans that supplied panels and bodies to Zagato and other small carrozerrie in Torino also built bodies for Apollo, completely by hand.

With production trickling in, IMC launched the new GT in Hollywood in March, 1963 and priced the car at nearly $7,000 – between Jaguar and Ferrari, a niche where the Apollo was the only competitor.

Initial reaction from the press was extremely positive: “Workmanship is of the highest quality,” declared Hot Rod. “Panels fit well, doors close with authority, and the interiors are comparable to cars costing twice that of the Apollo.”

Denise McCluggage, writing for Science and Mechanics (and a racing driver to boot) was pleasantly surprised to find “…the Apollo handles as well or better than a 2+2 Ferrari, an Aston Martin DB4, or a Sting Ray Corvette.”

But it was Road & Track (in a road test authored by Dean Batchelor) that identified the real flavor of the Apollo recipe: “During our testing, no less than eight full-throttle acceleration runs were made in the space of ½ hour, reaching 110 mph on several…To the car’s credit, the engine performed without a murmur, got nowhere near a dangerous temperature, maintained oil pressure and exhibited not a trace of clutch slippage. A lesson could be learned here by some of our noted “sports car” manufacturers…And it can be serviced...at any garage which has a capable mechanic, and parts for the running gear can be obtained at any Buick garage.”

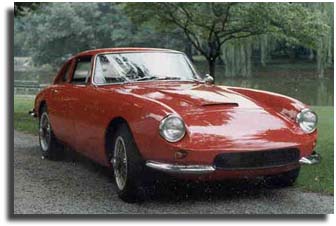

Brown, Davis, and Plescia had achieved their goal of an exotic Italian body with American reliability and power.

Sales followed at two cars per month – a brisk clip for a very low volume builder with a 6,000 mile assembly line. Among early buyers were entertainers Pat Boone and Larry Ramos (The Association). And professionals and doctors also bought Apollos because they could finally drive their exotic car to the office.

More power and performance came with the introduction of Buick’s 300 cu. in. V8 (5,000 cc), making the Apollo as quick as contemporary Ferraris.

However, being undercapitalized since the beginning, the company was always in search for investors; suitors came and went. But when a group backed away from granting a $96,000 loan after demanding production increase to eight cars per month, International Motor Cars simply ran out of operating capital after building 41 cars plus the prototype. At this point, Ned Davis pursued new investors, and production was put on hold.

Texas-built Apollos

A major dilemma faced the trio when forced to suspend Apollo production: How would they keep their coachbuilder, Intermeccanica, in business for when the doors opened again?

The answer came with an inquiry made by former sales manager George Finley. He had contacted Fred Ricketts – manufacturer of the Vanguard aftermarket auto air conditioning system – after see a prototype sports car Ricketts intended to produce and sell. He was anxious to cash in on his company’s relationship with over 500 auto dealerships and diversify Vanguard’s product line with a (somewhat) prestige sports car. However, fully engineering his “Warrior” and putting it into production proved more difficult than anticipated, so Ricketts lent an eager ear when Finley proposed a “fully engineered car ready for assembly.” This would dispose of the 19 body/chassis units that IMC couldn’t pay for and keep Intermeccanica solvent.

A quick deal with Vanguard Industries of Dallas, Texas allowed Frank Reisner to dispose of excess body/chassis units while Ned Davis sought new investors. The agreement stipulated that Vanguard’s cars must be sold under a different name, so Ricketts chose the unusual “Vetta Ventura” which means “high adventure” in Italian.

But Vanguard found the specialty auto business extremely difficult. Said Ricketts: “I couldn’t get any distribution.” Vanguard built 11 cars before selling the remaining 12 to shop foreman Tom Johnson to complete on his own over the next seven years.

Apollo International: Pasadena-built Apollos

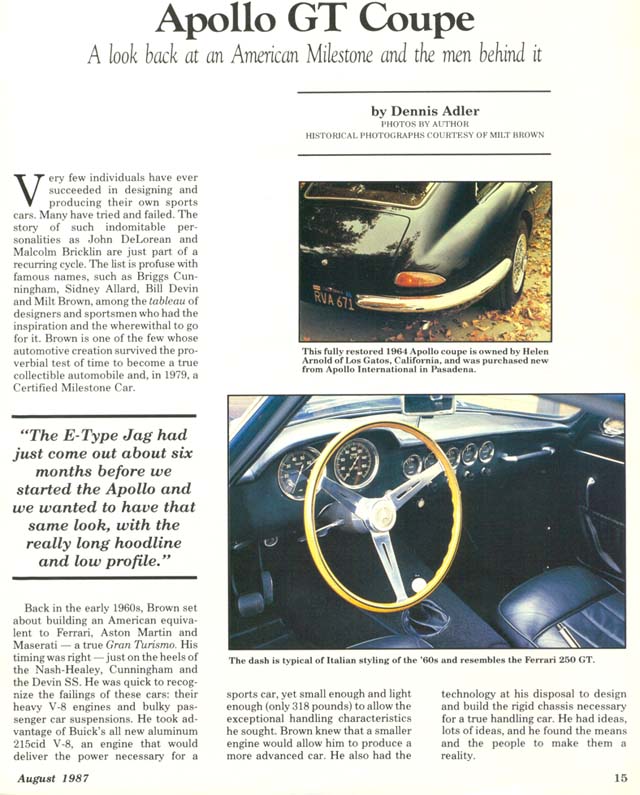

Meanwhile, Robert Allen, a probate attorney in Pasadena, California agreed to take over International Motor Cars’ liabilities and continue Apollo production. But, alas, this venture folded after a few months with about 14 cars completed. The six cars were assembled by shop foreman Otto Becker, and four cars left on the docks after Apollo International closed shop were eventually sold by US Customs. Two coupes and one convertible were completed by enthusiastic owners while the last convertible, during Milt Brown’s ownership, perished in the 1991 Oakland fire.

A total of 88 Apollos (plus one 2+2 and the prototype) were built during a two year run. “It was a winner because we could never make enough to satisfy the demand,” laments Brown. “We should have stayed small and charged more for out product.”

The Apollo was given milestone status by the Milestone Car Society in 1979. And every Apollo is highly coveted by its owner.